News from The Washington Post informed us that in Taiwan, parliamentarians threw pig entrails at one another. The beef (pun intended?) was over Taiwan’s government allowing imports of pig meat from the United States. Apparently, the Taiwanese object to additives in their meat. Using animal parts in protests is not new, in fact, there are some recent examples.

In 2012, here in the USA, a dead cat was used to make a political statement and garnered attention from across the global news networks. Jake Burris’ cat was killed.

Who’s Jake Burris? And why did his murdered cat make the global news?

To answer the first question, Mr. Burris works as Arkansas Democrat Ken Aden’s campaign manager. Not that Aden has a chance of winning. The third Congressional District in Arkansas is reported to be the most Republican district in the South, perhaps even the United States. Since 1967, only Republicans have held the seat (which, by the way, is home to the headquarters of Wal-Mart). In the last election, the current Congressman, Republican Steve Womack won 72% of the vote.

Which makes the killing of Burris’ cat ever more outrageous, and thus… newsworthy. Burris, returning home with his four kids in tow, stumbled upon his dead cat – its head bashed in and the word “liberal” painted on the side of its body. Sick.

But dead cats are the stories that History makes. It appears the killing of cats for political purposes has a long – if inglorious – past.

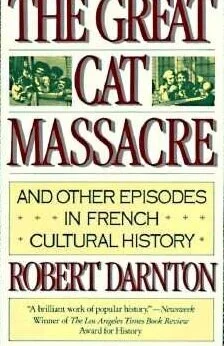

My first exposure to cat killing to score political points came in a 1985 book by American cultural historian, Robert Darnton. Entitled The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History, Darnton sought to explain why a worker’s protest (badly abused Parisian apprentices, in this case) in the 1730s rounded up, beat, put on trial, and then hung thousands of cats as a protest against their masters.

Later, while researching the London press regarding the American Revolution, I came across a little-known pro-Colonial paper called The Crisis. In sticking up for America, The Crisis took liberties is denouncing George III. Both the Court and Parliament ordered copies to be burned by the hangman in the Old Palace Yard and at the Royal Exchange. But on the 7th of March, 1775, thousands turned out to view the proceedings. However, when the hangman could not light the kindling, an impatient crowd pulled the city marshal from his horse. Suddenly dead cats, along with brickbats, and even articles of clothing rained down upon other nearby officials.

In a 1712 poem (“A Description of a City Shower”) by Jonathan Swift (author of Gulliver’s Travels) the Irish satirist starts with a “pensive cat.” No wonder, by the end of the poem, with the city in flood, outcome “sweeping from the Butchers stalls, Dung, Guts, and Blood, – Drown’d Puppies, stinking Sprats, all drench’d in Mud, – Dead Cats, and Turnip-Tops come tumbling down the Flood.”

A review of 1699 sodomy trials, also in London, revealed that dead cats were hurled at the accused. When one tried to break away, a large angry crowd tossed “Dead cats and dogs, offal, potatoes, turnips,” which bounced off the accused “from every side.”

When George Whitefield, the founder of Methodism, ventured from Bristol to proselytize in 1742 London, he found a tough audience. In a letter to a friend, he wrote, “there was some noise among the craftsmen, and that I was honored with having a few stones, dirt, rotten eggs, and pieces of dead cats thrown at me…”

Thus cats, especially the dead variety, were the early-modern era form of tossed insults. From the plague-ridden days of the fourteenth century, cats have held a bad reputation in Western societies. They “stole your breath,” walked in front you while black, possessed “nine lives,” and were known to spread malicious lies and rumors – or so said Dutch traditions. Cats were the favored pets of witches, and depending on how cats slept or washed themselves, they could foretell the weather.

Protests involving dead cats became common throughout Western societies by the seventeenth century and lasted well into the nineteenth. But it’s the twenty-first century. Dead cat politics supposedly died away more than a century and a half ago.

And yet, in Arkansas, in the backyard of our treasured retail giant known as Wal-Mart, dead cats rise from the not so “ain’t-that-quaint” file of History to once again adorn the power of protests. Spray-painting “Liberal” across the body of a murdered opponent’s cat, however, should not be the “return to values” in which the political right advances. If conservative rhetoric – in their pandering for votes from their base – remains emotionally based and devoid nary a whisper of rationality, I predict more dead cats. Sick.